How This Ancient Meditation Practice Changes My Day

In her book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard tells a few stories of men, women, and children who had been blind from birth gaining sight for the first time thanks to the rise of safe cataract surgery.

One 22-year old woman was at first so dazzled by the brightness of everything that she kept her eyes closed for two weeks. When she opened them again, Dillard writes, quoting the author who originally shared the story, the woman couldn’t recognize any objects, but “the more she now directed her gaze upon everything about her, the more it could be seen how an expression of gratification and astonishment overspread her features; she repeatedly exclaimed: ‘Oh God! How beautiful!’”

Another patient, a young girl, stands in front of a tree. Awestruck, she is utterly speechless until she comes up with a name for what she sees that just blows me away: “The tree with the lights in it.”

I would love to see the tree with the lights in it. Who wouldn’t want to experience that kind of freshness and awe? But I’m usually too distracted to pay attention. “Oh God!” comes out of my mouth at times, but it’s more likely to appear as an exasperated shout when our toddler dumps her whole dinner on the floor, or as a quiet mutter when I’m sitting in traffic. It’s much more rare for me to express amazement because I realize the miraculous beauty of everyday stuff around me — things like the first plants poking out of the ground after winter or a teenager quietly giving up his seat to a senior citizen on the crowded subway.

Recently, I actually witnessed those emerging plants and the subway kindness, but I didn’t take them in with intention or gratitude. Like many things in my day, they come and go, barely registering a blip on the radar screen of my life. I had to rack my brain to pull out details when I sat down to write this. As the poet T.S. Eliot wrote, I “had the experience but missed the meaning.”

In an effort to miss the meaning less frequently, and to break out of the unnoticing haze of busyness more often, I’m returning to a 500-year old meditative practice I have loved at various stages of my life: the “daily examen,” a form of reflection developed by St. Ignatius of Loyola.

Ignatius described the examen — a Spanish word that can be translated here as “examination of consciousness” — in his hugely influential work from the 1520s called The Spiritual Exercises. He requested that his companions — the very first Jesuits, a community of Catholic priests and brothers that’s now the largest such group in the world — complete it twice a day because he thought the practice was so important.

The heart of the examen, which is most often done at nighttime, is reviewing your day in gratitude, replaying the events of the day like a video recap in your mind. It’s not just a straight play-by-play from morning through evening, though. Instead, you’re mining your own experiences to notice gifts: moments or people or things that gave you a little glimpse of God at work in your life. The key idea is that there is always grace and goodness available to us wherever we are, but we often don’t notice it.

This focus on gratitude isn’t to say the examen papers over a day’s challenges — it’s not feel-good naivete. Painful experiences are essential to the examen so you can bring your whole self to the reflection. In my experience with the practice, meditating on my own woundedness this way helps me find God in the midst of tough situations, or allows me to invite God into a part of my life I’d been shutting him out of.

My favorite part of practicing the examen is that in the times of my life when I’ve committed to it consistently, its impact goes way beyond the 10 or 15 minutes I spend with it in the evening. I start to notice the little moments of beauty and meaning as they’re happening in real time. And when I’m aware of God’s presence in my life as it’s unfolding, I’m generally happier, kinder, more grateful, less bogged down by minor inconveniences.

I become more aware of patterns, too. One element of the examen is reviewing your shortcomings over the course of the day — not to beat yourself up, but to see where you might have room for growth. (I try to call to mind God’s gentleness and mercy when I get to this part!)

On a recent evening, I noticed during my examen that I had more than once been short with my wife about tasks she had asked me to help with during the day. After I caught that slip-up, I thought about why I might have fallen into that pattern. I called to mind how much my wife does to keep our family running and how I probably contribute less than I think I do. I can let that realization improve my response the next time she asks me to do something. Without the examen, my impatient episode would have faded into memory with the hundreds of other small hurts and slights that come with marriage. But by noticing it and bringing it to spiritual reflection, I can learn from it and become a better husband and person.

When I think about the benefits of the examen, I call to mind a scene from the movie Lady Bird, which tells the story of a Catholic high school student in Sacramento, California. In the scene, a religious sister who teaches at the school tells the title character that she so clearly loves her hometown. This surprises Lady Bird: “I do?” she asks.

“You write about Sacramento so affectionately and with such care,” the sister replies.

“I was just describing it.”

“Well, it comes across as love.”

“Sure, I guess I pay attention.”

“Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing? Love and attention?”

Maybe love and attention aren’t exactly the same thing, but I know I get better at love — loving God, loving my family, loving my co-workers, loving myself, loving the world — when I’m paying better attention to the instances of grace and beauty in my life. And nothing helps me pay attention like the daily examen.

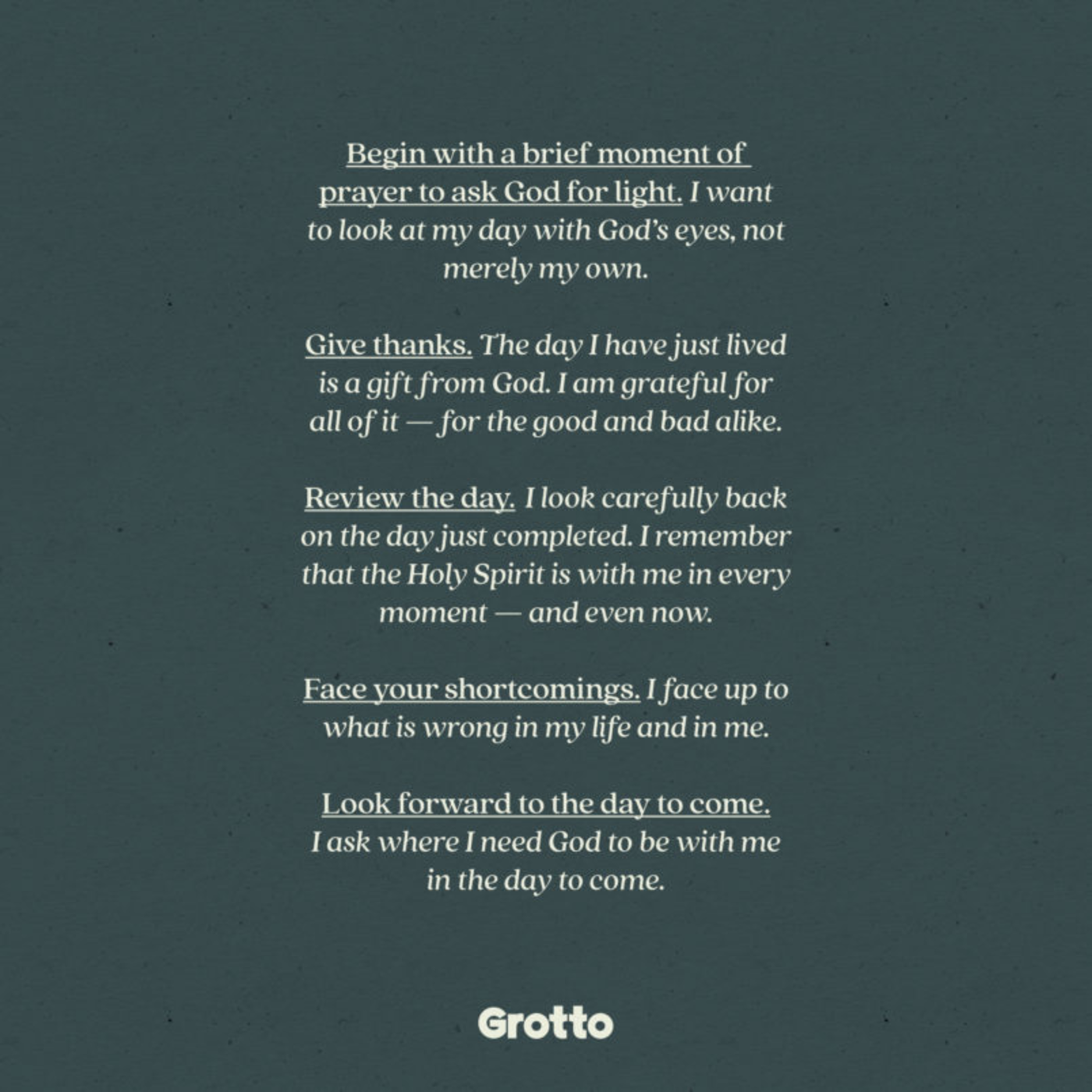

Try the daily examen yourself — it’s a very simple process. There are lots of versions out there, but I love this one based on a book by Jim Manney.